Return of the Robber Barons: Class, Labor and the New Gilded Age

A Lesson from the Long Memory of Labor's Past

“In every age it has been the tyrant, the oppressor and the exploiter who has wrapped himself in the cloak of patriotism, or religion, or both to deceive and overawe the People.” ― Eugene V. Debs

Unimaginable riches. Flagrant corruption. Crushing poverty. Unprecedented industrial growth. Anti-immigrant propaganda. Voter suppression. Violence against workers. An extraordinary amount of money injected straight into the veins of American politics. Its 1901 and President Teddy Rosevelt is about to enact the Sherman Antitrust Act and two new wealth taxes, the estate and capital gains tax to combat the concentration of wealth generated by the robber barons of the Gilded Age. Today, these couple of sentences are as true as they were 100 years ago. With the campaign to make America gilded again, “Solidarity” as Harry Bridges puts it, is once again, “the most important word in the language of the working class.”

Opulence isn’t unique. The streets of heaven and the tomb of Tutankhamun are both lined with gold. The dollar bill is so mind–numbingly uninteresting that you need millions of them to be special. Yet the hoarding of wealth by monopoly capitalists shapes every aspect of our life.

Ancient kings were certainly rich. Reportedly the House of Saudi is richer than most of history’s greatest emperors and feudal lords, and the net worth of Mansa Mali, long considered the richest man in history, when adjusted for inflation is in the ballpark of Elon Musk. Reportedly King Solomon would be a modern day trillionaire, a title that several American billionaires are projected to reach during the current administration–an accomplishment that the House of Saudi is speculated to have long surpassed.

Modesty was actually revered for a brief time in American history. Early aristocrats rebelled against the opulence of kings and queens, preferring the low profile of austerity, rather than flaunting their wealth. Humility was considered a sign of high character. While rejecting the birthright opulence of England, early Americans began to favor consumer-based aristocracy, buying status instead of being born into it. In the process they dismantled any ideals associated with humility or austerity.

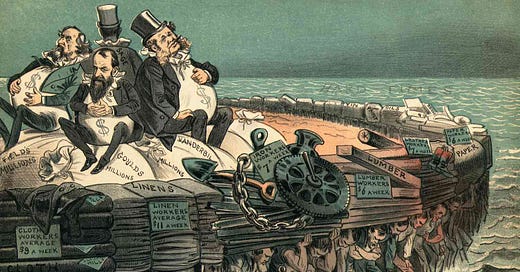

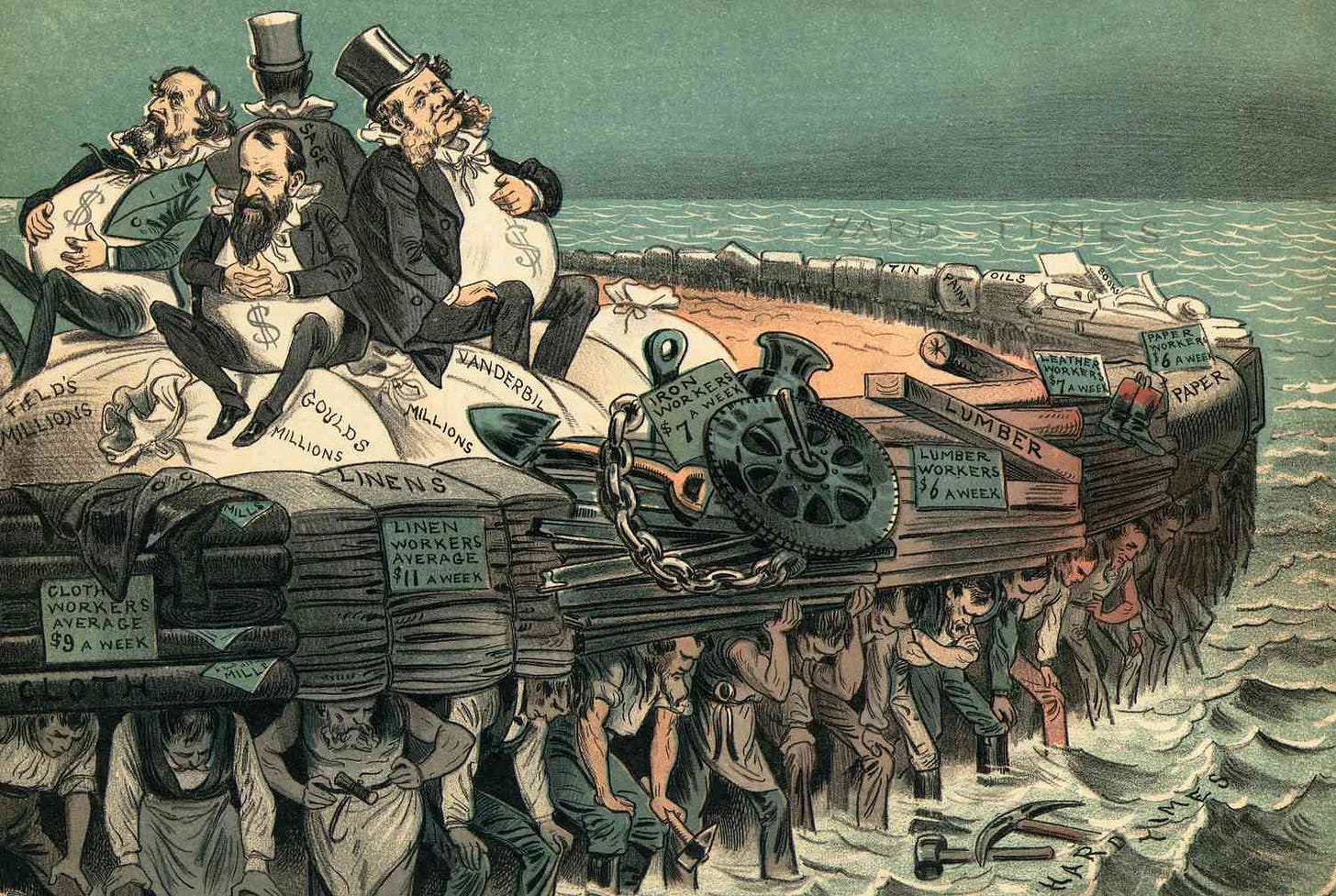

The original Gilded Age saw unprecedented industrial growth, growth that produced massive wealth inequality and a new era of worker dependency. With industrialization, workers moved out of the agricultural sector and into factories, becoming dependent on earning a living, rather than just living. Increasingly food was purchased not grown, and business crept its way in between every interaction, giving bosses power not just over a worker’s time, but over their ability to live. Laissez-faire capitalism, or more aptly named unregulated capitalism, became the playground of the obscenely rich. This doctrine propelled the idea that government only inhibits economic success. In that spirit, the Gilded Age was an era without income tax, inheritance tax or any tax on corporate earnings. The free-for-all of growth cemented the new status-through-consumption ideal, one that purchased virtue, told workers that productivity was patriotic and that growth was godliness–an ideology that is arguably stronger today than ever.

“Growth for the sake of growth is the ideology of the cancer cell.”

– Edward Abbey

The industrialization of production brought with it unprecedented growth and unbelievable wealth for the chosen few. For the working masses, it brought the industrialization of exploitation and in turn poverty. Once workers sold their time and labor, modern poverty was created. It's not that people had never been poor, there’ve always been have-nots, but through industrialization, the basic needs of existence, food and water, became inaccessible without money–and therefore without selling one's labor. For better or worse, in an agrarian society, workers live a more independent life, they are forced to be self-sufficient, but in turn lack many of the benefits of modern society. But Industrialization breeds dependency on itself. Industrialization removed the option to be autonomous or self-sufficient. In the digital age, instead of removing the ability to be autonomous from industry, they have removed the ability to be autonomous from technology.

Just because business was unregulated doesn’t mean that the original class of robber barons didn’t need political sway to exploit labor. In post Civil War America, businesses sprinted West, tapping into new natural resources. Railroad builders, mine owners, and steel producers lobbied and often bribed their way into positions to amass fortunes. With no government regulation, there was nothing to stop industry-wide monopolies and the exploitation of workers, not to mention a new and seemingly never-ending supply of immigrant laborers.

Enter Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller and JP Morgan among others. Like the feudal lords before them, exploitation was their bread and butter. The term robber baron first appeared in the middle ages, describing feudal lords known for extorting travelers through excessive tolls. Instead of land ownership, these new titans of industry employed monopolistic business models while manipulating the levers of government to slide the scales in their favor.

Campaign contributions, lobbying and even bribery-notably Leland Stanford of the Central Pacific bribed congress, Thomas Edison offered $1000 a piece to the New Jersey legislature to do his bidding and Jay Gould, hailed are perhaps the most ruthless of the lot, paid Abel Corbin, the husband of Virginia Grant, to influence her brother, President Ulysses S. Grant.

As you might expect, these tycoons faced little to no legal consequence. Eventually their flagrant disregard for the rules, displays of wealth and the mounting press coverage issued by journalists swayed public opinion against them. But even that only led to their concerted effort and financial investment into controlling the apparatuses of media. Enter one of America’s greatest marketing campaigns, philanthropic capitalism, or the idea that business owners can still be relatable, good guys even if their business practices are vicious.

Arguably one of the most sympathetic of the lot, Andrew Carnegie is described as “One of the most important philanthropists of his era.” He was a self-made man by any modern definition of the concept. He built a truly massive steel empire while cultivating the image of a benevolent capitalist and philanthropist. “Cut the prices, scoop the market, run the mills full, watch the costs, and the profits will take care of themselves” Carnegie would say. His empire was built running two shifts of workers, each working twelve hours straight for twenty-four hour a day steel production. As production increased and the demand for steel increased, workers watched their wages drop more than 30%–presumably as part of Carnegie’s “watch the costs” concept.

With the mounting tensions of wage theft, safety risks and diminishing basic rights, friction between the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers and The Carnegie Steel Company finally hit a head in 1892 with the Homestead Strike. While publicly supporting unionism, Carnegie, while in Scotland on holiday, ordered the plant to manufacture enough steel to weather a strike and to stop recognizing the union. Carnegie also agreed to implement manager Henry Clay Frick’s plan to employ the Pinkertons, a private security company, to break the strike. Three hundred Pinkerton agents were brought in, given badges that read "Watchman, Carnegie Company, Limited" and armed. After a standoff and ensuing battle, sixteen people were killed, including three Pinkertons.

John D. Rockefeller Jr. was also regarded as a philanthropist. Junior was the son of Standard Oil’s famed John Rockafeller Sr–the first billionaire. Standard Oil was broken up into thirty-four other companies after violating antitrust laws–which would diminish the families control of oil but increase their wealth. Modern staples like ExxonMobil and the Chevron Corporation are products of that breakup. Today, the philanthropic efforts of the Rockefellers dominate any recounting of their life and accomplishments.

In 1902 John D. Rockefeller purchased the controlling stake of the Colorado Fuel & Iron Company. Nine years later he handed the company over to his son and namesake, John Jr. Facing dangerous work, low wages, and poor conditions, many colliers joined the United Mine Workers of America. In 1913 the UMWA presented their demands, which included union recognition, an 8-hour work day and stricter safety enforcement among others. The CF&I refused and a strike ensued. CF&I and the Rockefellers hired a detective agency, described as “Texas desperadoes and thugs,” who after several days opened fire on the strikers. During the fighting, four women and eleven children hid in a pit beneath a tent, the militia set the tent on fire killing all but two of the women. The Colorado Coalfield War, as it was later called, killed at least seventy-five. In a United States Commission on the Industrial Relations report, Rockefeller Sr. stated he would have taken no action to stop the attacks. The one action Rockefeller was willing to take was hiring PR expert Ivy Lee to change the way Americans viewed the Rockefeller name and brand moving forward, rebranding the family as altruistic capitalists, peaceful liberals and most importantly, philanthropists.

John Pierpont Morgan was so adept at extracting value from labor and consolidating monopolies that his approach to maximizing shareholder profits became known as Morganism. Jay Gould was synonymous with watering stocks–or creating artificial stock market value. Cornelius Vanderbilt built his empire on exploited railroad labor, today his name is as well known for a prestigious university as anything. At every step the mythology these robber barons created is at odds with the reality of what it means to be a robber baron.

If a robber baron by definition consolidates industries into monopolies, exploits workers, and manipulates the market through manipulating politicians and controlling the narrative of media, then the new barons are right in line with their predecessors.

"Wall Street owns the country. It is no longer a government of the people, by the people, and for the people, but a government of Wall Street, by Wall Street and for Wall Street... Our laws are the output of a system which clothes rascals in robes and honesty in rags.” – Mary Elizabeth Lease

At the inauguration this past January, standing front and center, were the new reigning class of robber barons; Mark Zuckerberg, Jeff Bezos, Sundar Pichai, Tim Cook, Shou Zi Chew and of course the world’s wealthiest man, Elon Musk.

It has been suggested that the current war on the working class is a backlash to the progressive gains workers accomplished during the pandemic. After the shut down, when essential and nonessential workers were separated, many with the privilege to do so flexed their labor muscles to stay home, avoid contact with co-workers and reconstruct their working lives. It has been well documented that the move back to office was fueled by control and not productivity, and with that, the short lived admiration for “essential work” was stomped out. However, the shift in perspective that many workers experienced during the pandemic has proven much harder to walk back than regulations.

Big Tech is in the business of control. They’ve injected themselves in between every human interaction. When you text your parents, order dinner with your kids and watch a show with friends, Tech is part of that experience. There is no corner of culture or modern life that Big Tech hasn’t infiltrated and extracted wealth from. The new class of barons are equally ruthless in business and politics as their predecessors, and they share the same desire to wield unrivaled power and enjoy universal admiration. Emergent industries almost always experience a lap in regulation, which creates opportunity for those with the resources and access to exploit those loopholes.

The end of the Gilded Age was marked by the rise of the Progressive Era and ultimately World War I. The end of WWI was marked by the red scare. Coming out of WWI, unionism was on the rise–it would eventually reach its peak with 35% of the labor force unionized in the 1950s. But on its way up, industry leaders recognized the impending threat. While unions aren’t inherently Communistic–in fact ideologies and doctrines between Socialism, Communism, and Anarchism between Industrial and Craft unionists are always a heated debate, but the red scare as it would be known, saw widespread political persecution and the ousting of anyone in government with any association to left-wing policy or action.

The first red scare pointed the finger at Communism, Socialism, the American labor movement, Anarchism and political radicalism in any and every form. A tenant of barnonism is controlling the direction of blame. The real question is always, whether or not your lack is the result of those at the bottom of the system who have nothing, or those at the top of the system who have everything? The first red scare aimed to point the blame at any organization or ideology that put the well-being of workers over the well-being of business owners. Today, Woke is the new Red.

In the wake of the MeToo movement, George Floyd protests, Black Lives Matter, the Women’s March, and mass resignation–which could better be described as workers standing up for themselves, the new class of robber barons implemented a new red scare, one that points at Wokism as the cause of every American’s real problems. No more logical than the original red scare, this battle keeps society engrossed in a culture war rather than asking why corporate profits can reach record highs but their wallets and stomachs are still empty.

While the Progressive Era rose from the ashes of the Gilded Age, it was labor organizers, investigative journalists, women's suffragists and working people of all stripes who brought the fight to the robber barons and built the foundation for a new era. It was also a time where politicians like Franklin D. Roosevelt and his constituents introduced antitrust laws, taking on monopolies and the barons who wielded their power. Social Security was introduced in 1935 as a direct result of the wealth inequality and crippling poverty of the Gilded Age. While many of the social programs that we’ve come to take for granted, until recently, were the clear work of labor power meeting legislative willingness, the fight against oligarchy started much earlier. In the late 1800s the Independent Labor Party started to grow by voicing the clear problems of big business’s influence on government. Fighting to put workers before shareholders, the party found some success but ultimately was unable to crack the self-sustaining two-party political system.

“Never be deceived that the rich will allow you to vote away their wealth.”

― Lucy Parsons

Extreme inequality generates opportunity, one that we likely haven’t seen since the original Gilded Age. However, it requires working people to join together, drop the culture war, and understand that farmers, factory workers, teachers, tradesmen, graphic designers and medical workers all have the same interest. It requires the understanding that in rural and urban environments, in blue and red states, workers have more in common than they do in opposition. It requires workers to remember that labor generates all profit and that management is only capable of increasing sales or reducing costs. We must recognize that the robber barons, both old and new, are content to put their full weight on the scale to grind every last dollar from labor. And perhaps most importantly, it’s crucial to remember that the National Guard has never been called to hobble the ruling class or to slow the wheels of exploitation. They have, time and time again, been used to break strikes, suppress dissent and silence protest. So we stand together, or we won’t stand for long.

Likewise we have to recognize that these robber barons aren’t two dimensional cartoons. They are three dimensional people who exploit labor and make jokes, they break strikes and resonate with culture, gut departments and smoke weed on podcasts. They launch relatable working class marketing campaigns and refuse to give their workers basic rights. Carnegie, arguably the most sympathetic of the bunch, built libraries and cultural centers, institutions that his workers couldn’t afford to visit or even have the free time to enjoy. Vanderbilt has a college that not one of his workers could afforded to attend. In a system that generates wealth by exploiting labor, even philanthropy is extracted from one group for the benefit of another.

In the industrial age, workers sold their labor and robber barons bought it as cheaply as possible. Today we give our labor, creativity, ideas and data to these billion dollar platforms for the promise of attention and another ticket to the online lottery, hoping once again to defy all odds and transcend exploitation.

“I am opposing a social order in which it is possible for one man who does absolutely nothing that is useful to amass a fortune of hundreds of millions of dollars, while millions of men and women who work all the days of their lives secure barely enough for a wretched existence.” ― Eugene Debs

In A History of America in Ten Strikes, Erik Loomis writes, “Once again, we have a society where our politicians engage in open corruption, where unregulated corporate capitalism leads to boom-and-bust economies that devastate working people, where the Supreme Court limits legislation and regulations meant to create a more equal society, and where unions are barely tolerated. Life has become more unpleasant and difficult for most Americans in our lifetimes.”

In a time where we once again face the onslaught of oligarchy, the long memory of how we’ve endured, resisted and defeated this playbook in the past is our best tool. Solidarity is once again more than a word, it is a weapon. The working class has never had the money to fight tycoons at their own game, but by seeing ourselves as one, we can fight back the tides of exploitation. Through collective action the scales can be balanced, but it is anything but light work. Those who stood down the original Gilded Age faced backlash, both legal and personal, the loss of employment, incarceration and even death.

As aesthetically pleasing as invoking the political action of the past may be, it is unlikely that this Gilded Age will come to a halt the same way the first did. The digital era presents new obstacles, but the biggest fundamental message that should be gleaned from the direct action of the working-class 100 years ago is that it requires more than just working class action, it requires unrelenting solidarity. It was Jay Gould the stock waterer who bragged he could “hire one-half the working class to shoot the other half to death.” This mentality is alive and well in the social media carnival that is our modern political world.

Direct action must encompass both political legislation and the mobilization of mass solidarity among working people. To the “bore from within” or “pressure from outside” debate I say “Yes and.” Both are required to invoke change. But change by nature isn’t permanent, like our predecessors, the minute we take our collective foot off the gas we lose ground. It is an uphill fight against a massive machine, make no mistake, but it is not impossible. And it starts with ALL working people coming together to make the exploitation of themselves unprofitable.

The end of the original Gilded Age in America is often credited to the political leaders who passed legislation–and fair enough they deserve credit. It requires law to cement change. But decades of working class struggle from the unnamed masses lifted those changes out of the dirt and into existence. For their efforts most weren’t even documented by name.

In the Progressive Era, America witnessed an explosion of union support and a robust working class–one that in many ways left women and people of color behind. This time, it will take the solidarity of all working people, no division, no group excluded, standing together shoulder to shoulder and hand in hand. It will require working people to no longer let the barons pay us to step on each other’s necks. It will require working people to see all workers, from immigrants to office workers as one labor class. And it will require us to put being good members of the working class before being good workers. In the words of Mary Elizabeth Lease, we will need to “Raise less corn and more hell.”

“While there is a lower class, I am in it.

While there is a criminal element, I am of it.

While there is a soul in prison, I am not free.”

― Eugene V. Debs